Editor’s Note: Time Through the Ages is a four part series written by Andrew Canter, member of the British Horological Institute, Alliance of British Watch & Clock Makers, and the British Watch & Clock Makers Guild. In this third installment, Andrew focuses the growing influence of China on the west, and the importance of Chinese trade on horology through much of the 18th century. For more from Andrew, check out his work at Mr. WatchMaster.

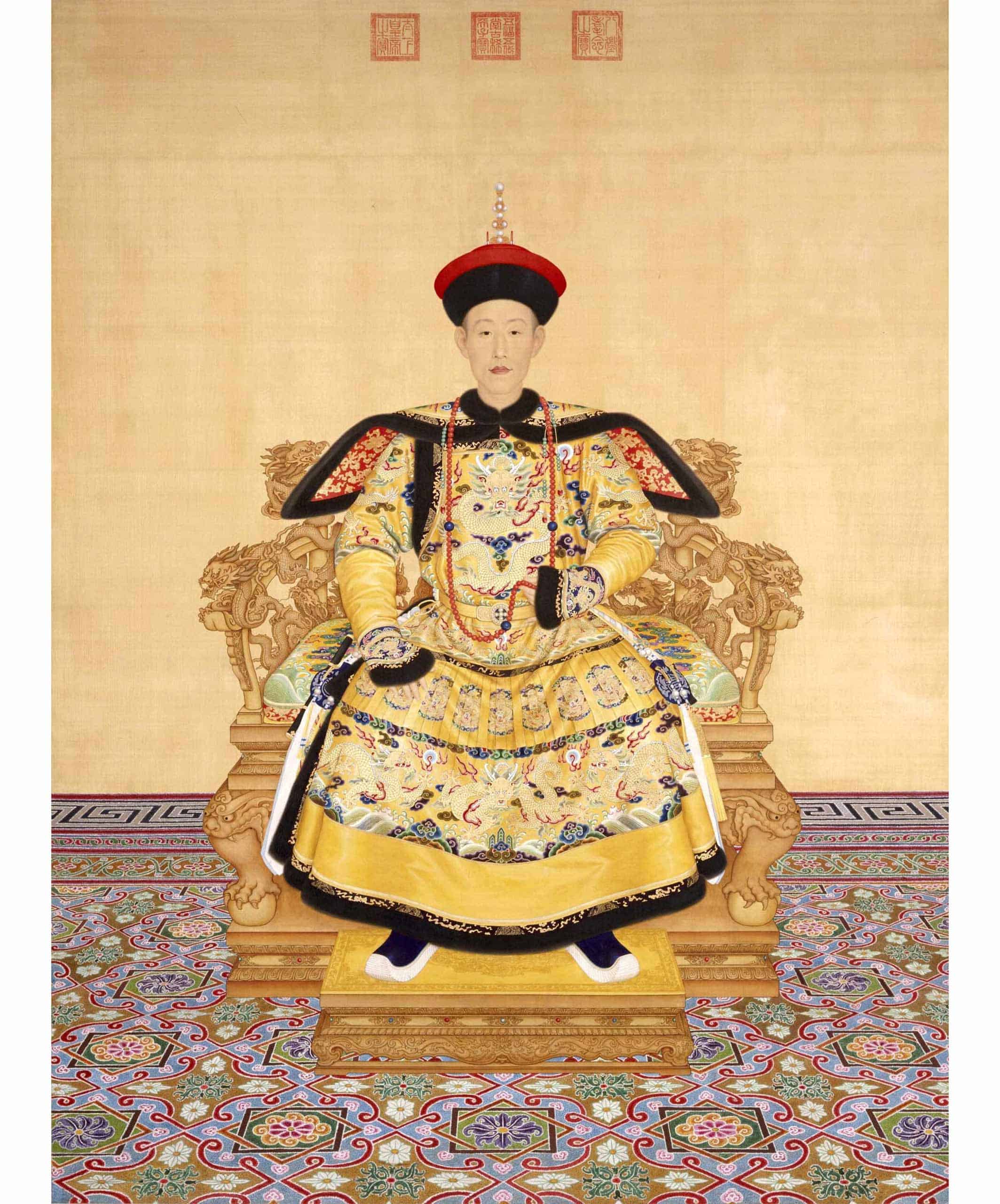

The Chinese term Zimingzhong broadly translates to ‘bells that ring themselves’ (which came to be known in Britain as ‘Sing Songs’) and refers to antique clocks, typically made in England for export to China during the Qing Dynasty, primarily in the 17th and 18th centuries. These clocks were especially made for emperors’ Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong and were known for their intricate design and mechanical sophistication. One key aspect of the emperors’ fascination with western timepieces was their accuracy. These clocks played a pivotal role in assisting the emperor and his court astronomers in timing celestial events, such as eclipses. The ability to track and predict celestial movements not only showcased the emperors’ mastery of the heavens but also served to validate their divine right to rule.

Beyond celestial observations, the emperors used these timepieces to manage time within the palace. It is interesting to note that in the 1700s, China and Britain measured time differently. In China, the day was divided into ‘shi’ (double hours) and ‘ke’ (quarter hours), while the night was segmented into five ‘geng’ (night watches). In contrast, Britain adhered to a 24-hour system. Despite this disparity, the shared reliance on the movement of the Sun facilitated an easy conversion between the two systems.

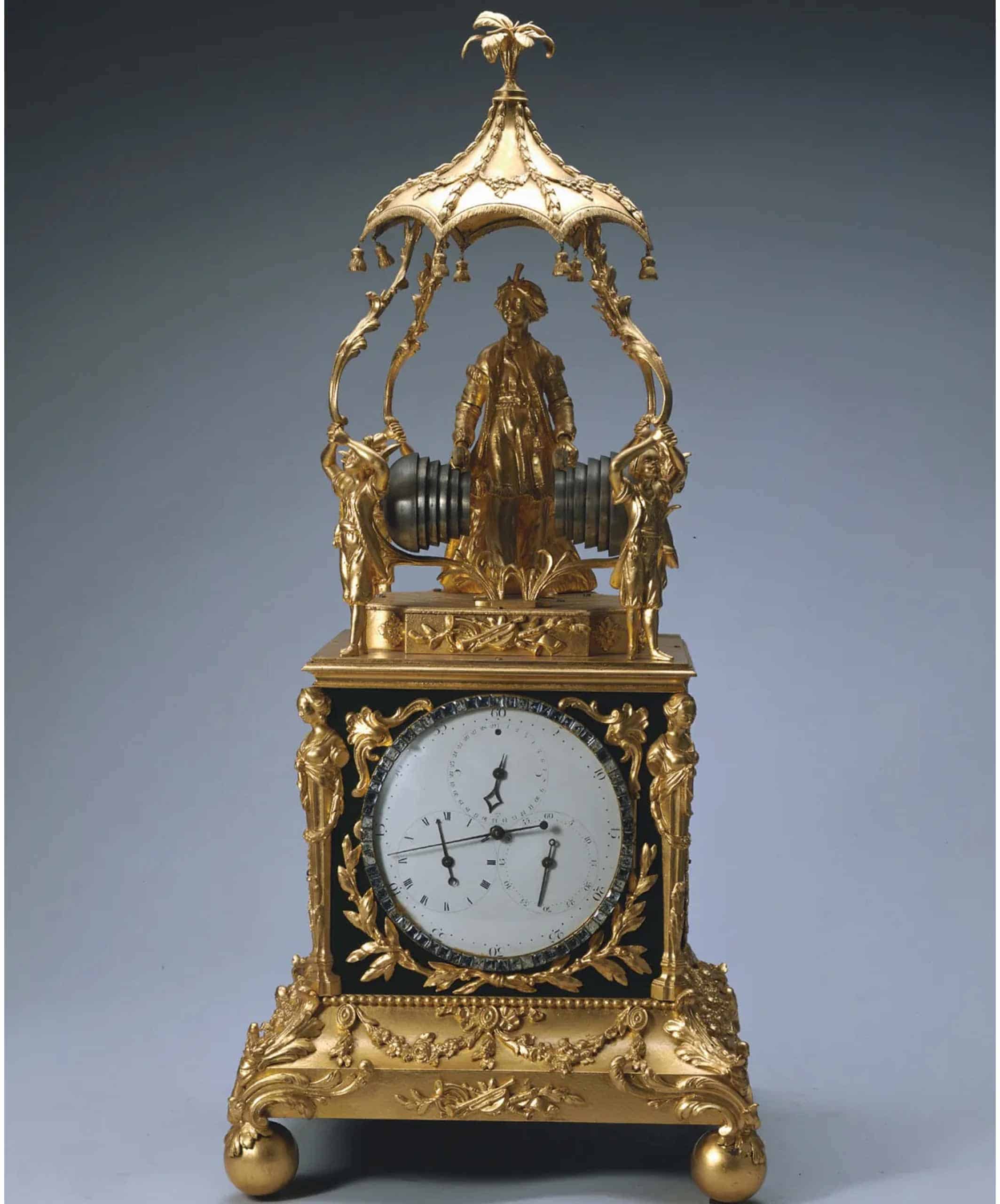

They often combined Chinese artistic elements with Western clock-making technology, reflecting a blend of cultural influences. Many zimingzhong clocks were highly decorative, featuring elaborate carvings, precious metals, and intricate paintings. They were not only functional timepieces but also symbols of wealth and status.

These extraordinary clocks were highly prized in Chinese society, often found in the homes of the wealthy and in the imperial court. They were symbols of technological advancement and luxury. Zimingzhong clocks incorporated advanced mechanical features such as chiming mechanisms, automata (moving figures), and intricate gear systems. They often played music or featured scenes with moving figures when they chimed.

The introduction of these clocks to China was influenced by European missionaries and traders who brought, primarily, English clock-making techniques to the Qing Dynasty. This led to a unique fusion of Western mechanics and Chinese artistry. The design of these clocks reflected Chinese aesthetic values, with detailed artwork and craftsmanship. Many included traditional Chinese motifs, such as dragons, phoenixes, and scenes from nature. These clocks represent an interesting intersection of culture, art, and technology, showcasing the historical interactions between China and the West.

Perhaps one of the best known and most flamboyant makers was James Cox (1723-1800). Cox was a jeweller by trade but above all was an entrepreneur who designed unique artefacts and contracted to have the components made by craftsmen in the various horological, mechanical music, automaton, and decorative arts trades. He brought together an unprecedented network of independent craftsmen to supply the East with an unrivalled number of innovative and opulent timepieces.

It wasn’t just clocks that were exported to China for the wealthy. This exquisite gold, partly enamelled automaton pocket watch (below) is set with gemstones and was made by Cox in 1770. When activated, the eight rosettes, or stars, spin within the rotating frame on the dial of this watch, which is pavé-set with paste jewels.

The trade in clocks between Europe and China was a fascinating aspect of the broader exchange of goods, ideas, and culture during the Qing Dynasty. The trade in clocks and other timepieces serves as an example of how luxury goods were used in diplomacy and cultural exchange. Clocks were often used as diplomatic gifts. European envoys and missionaries, such as those from the Jesuit order, presented elaborate timepieces to the Chinese emperor and his court. These gifts were intended to impress and gain favour, facilitating trade and missionary work.

Possessing a European clock became a status symbol among the Chinese elite. These clocks were often displayed prominently in homes and served as a testament to the owner’s sophistication and connection to the broader world. Inspired by English and other European timepieces, Chinese artisans began to produce their own versions of these clocks. They often incorporated Chinese artistic elements, blending European mechanical techniques with traditional Chinese aesthetics. Guangzhou (Canton) became a centre for the production of such hybrid timepieces.

Part of the appeal of zimingzhong was also the sophisticated music technology they showcased; they often played a selection of popular European or Chinese songs. Skilled programmers would convert written musical scores into mechanisms. It’s extraordinary to note that most Britons had never ventured to China or interacted with its people. The designs often came from European travel writings and imported Chinese products, which in turn carried their own assumptions about European culture.

One of the most notable decorative styles of the period, Chinoiserie, emerged in Europe, drawing inspiration from China, India and Japan. This aesthetic, exemplified in zimingzhong featuring a turbaned figure (see above), reflected an idealised and often unrealistic view of distant nations.

The trade in clocks during this period exemplifies the complex interactions between China and Europe. It highlights how luxury goods were more than mere commodities; they were instruments of diplomacy, symbols of status, and catalysts for technological and artistic exchange. This period laid the foundations for continued interactions and mutual influence between East and West in the centuries to follow.

The decline of the Chinese clock trade in the 1700s can be attributed to several interrelated factors, including changes in political dynamics, shifts in trade policies, and advancements in local clockmaking. There were significant political and diplomatic changes which included the end of the Jesuit influence and missionaries who were instrumental in introducing European clocks to China, acting as intermediaries who saw their influence wane by the mid-18th century.

Also, the Qing Dynasty increasingly consolidated its power and became more self-reliant. The initial enthusiasm of the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors for Western technology diminished as they established stronger control and sought to promote Chinese traditions and innovations. Ultimately, the Qianlong emperor implemented restrictive trade policies which reduced the opportunities for direct exchange of luxury goods like clocks between European traders and the Chinese elite.

Over time, Chinese craftsmen became adept at producing their own clocks. Initially inspired by European designs, they developed their own techniques and styles, reducing the dependency on imported timepieces. This initial period of fascination with Western technology led to the integration of these techniques into Chinese craftsmanship. Once the novelty wore off and local production improved, the need for imported clocks decreased.

The end of the Chinese clock trade in the 1700s was the result of a complex interplay of political, economic, and cultural factors. This period underscores the dynamic nature of international trade relationships and the impact of broader historical trends on specific economic activities. Finally, in 1796, Emperor Jiaqing ascended the throne; he believed zimingzhong to be a frivolous waste of money and the trade faded.