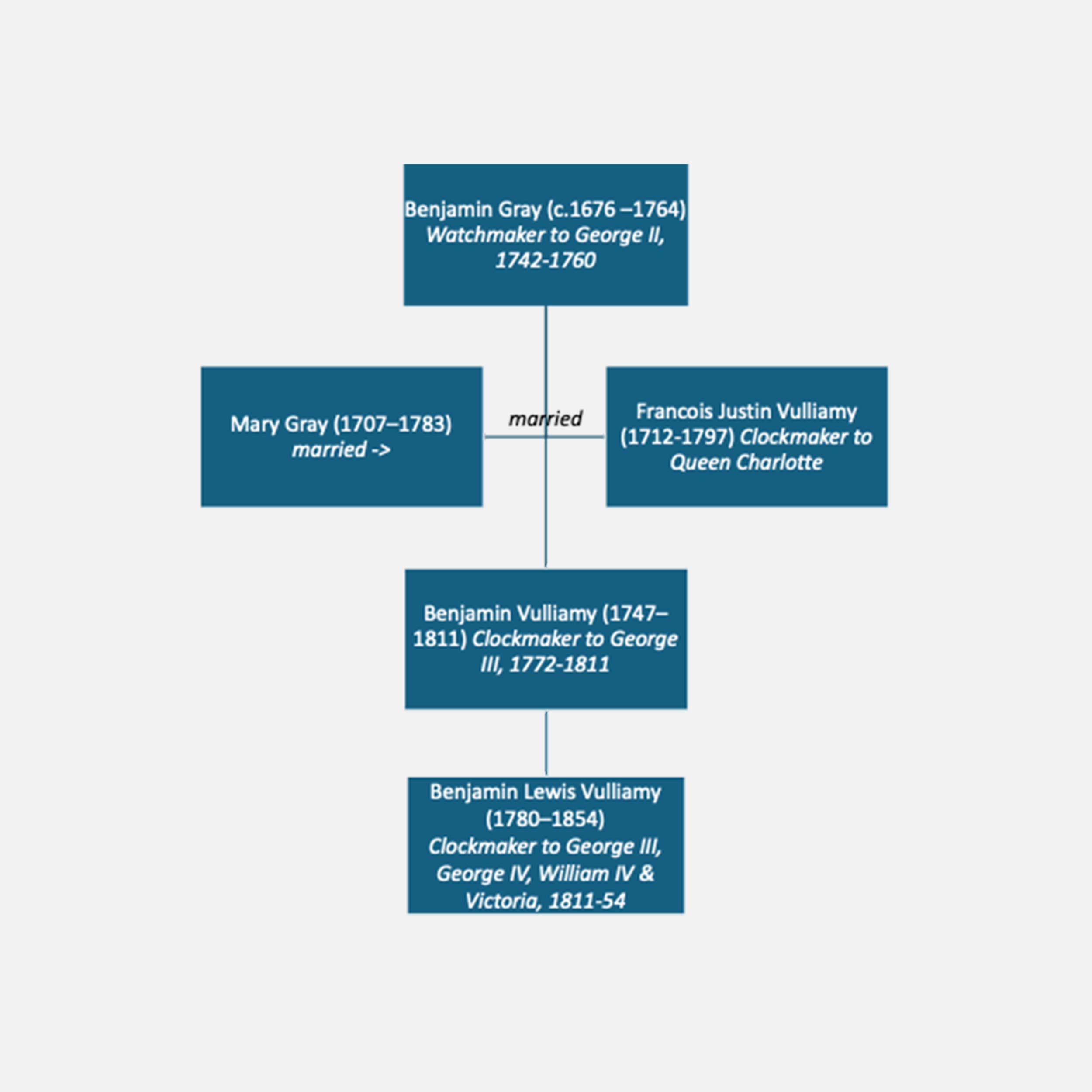

Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy was the last of the great Vulliamy family of Royal clockmakers and five-times Master of the Clockmakers’ Company. He was Royal Clockmaker to King George IV, King William IV and Queen Victoria and the driving force behind the formation of the Clockmakers Library and Collection – now Clockmakers’ Museum – from 1814 onwards.

The Public Face of Clockmaking

The Vulliamy family was known for producing high-quality timepieces, often regarded as some of the finest in Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy was the last of four generations of Royal clockmakers based at 68 Pall Mall, London from 1753. Early in life he joined his father Benjamin in the family business, which by then was best known for its ornamental clocks and metal furnishings. Upon his father’s death in 1811, Benjamin Lewis inherited control of the business. Following the end of the Napoleonic wars he began to shift its output towards emerging new markets, particularly those brought about by the development and expansion of institutions like the new Houses of Parliament, government departments and London’s clubland. In all his products he aimed for high quality, reliability and accuracy. He created clocks for public buildings and important institutions. Some of his works are still present in places like the Horse Guards Parade and the Royal Exchange in London.

This magnificent and imposing clock No. 1394 (below) was purchased for use in the General Register Office at Somerset House, which was operational from 1837 to record births, marriages and deaths for England and Wales.

It was one of many government offices that Vulliamy won the contract for to supply clocks to a particular specification. The clocks were often emblazoned with the Royal monogram and the institution’s names as is the case with this example.

Vulliamy was also known for crafting exquisite ornamental clocks, often influenced by classical architectural designs. Many of his pieces combined art and precision engineering, featuring elaborate decorations with materials like marble and bronze as detailed in the clock below.

Egyptian ornamented clock signed ‘VULLIAMY LONDON No 438’. Made c.1807. Image courtesy of the V&A Museum South Kensington

The figures of Horus (an ancient Egyptian God) and the serpents that decorate the base come from plates in Vivant Denon’s Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte, published in London in 1802. The Vulliamy clockmaker’s account book lists the craftsmen who worked on the clock and the amounts they were paid: a craftsman named Houle was paid £8 for ‘chasing the Sphinxes’ (modelling them with a hammer and steel tools); the movement was supplied by a craftsman named Jackson and only cost £5 10s. The clock was sold to Princess Mary on the 5th of June 1812 for 50 guineas (approx. £4,000 today).

His study and experience of turret clocks caused Sir Charles Barry to consult with him regarding the construction and arrangements for the building of the clock tower for the Great Clock at Westminster, otherwise known as Big Ben, and he later submitted a design for a clock to go into that tower. Ultimately this was unsuccessful as the contract was awarded to Edward John Dent.

His clocks were not only functional but also works of art, like the above example. This boule clock has a waisted case veneered in red turtle shell and inlaid in brass, the ormolu mounts with paw feet and shell casting to the top, the rear door having a pierced gilt fret finely engraved with a scroll and floral design.

Moving into the Victorian age, he took advantage of changing tastes making a series of clocks cased in Coalport Porcelain (founded in 1796). The elaborate pink ground porcelain case is set with exotic birds and flowers on scroll feet, with gilded scrollwork and lattice work. Not to everyone’s tastes, but they certainly standout.

Decorative porcelain cases like this were fashionable in the first quarter of the 19th century and the early Victorian period, and Vulliamy produced several clocks of this type. At least two were purchased by the Royal family and are still in the Royal Collection today.

The Founding of the Clockmakers’ Museum Collection

The first meetings of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ Library Committee were held at the Vulliamy’s premises at No. 74 Pall Mall. This is where the newly collected horological books were stored. Each member of the Committee presented books and other relevant items. Benjamin Lewis searched stalls and bookshops for rare and interesting works. He also attended auctions, most notably, the sale of Alexander Cummings property, where he purchased on behalf of the Clockmakers’ Company, a silver half-seconds beating watch (below) which was described as ‘an original Lever Escapement watch with verge – vibrates 1/2 seconds –supposed unique invention’ at a cost of £3-0-0, and a timekeeper that Cumming had made for Capt. John Constantine Phipps’ voyage towards the North Pole in 1773. They were added to the Library Collection.

Verge watch by Peter Debaufre with later modification by Alexander Cumming, London c.1700. The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce © The Clockmakers’ Charity

Once the principle of setting up a ‘library’ of objects had been established, watches and movements began to flood in. Vulliamy himself gave seventeen ‘specimens of the art of watchmaking’. In 1817 Benjamin Lewis bought a ‘mahogany bureau and bookcase’ which had been commissioned in 1795 from celebrated furniture makers Gillows of London. This is still owned by the Company and is on show at the Clockmakers’ Museum in South Kensington, London.

In 1819, five years after the library was formed, the Committee reported that it had acquired 110 books, 48 watches or movements, and 12 manuscript drawings amongst other items. Today, the Clockmakers’ Museum continues to acquire important horological items and remains the oldest surviving collection of clocks and watches anywhere in the world.

Often placed in the homes and pockets of the wealthy and influential, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy’s legacy is associated with both precision and the beauty of his timepieces.

Duplex Pocket Watch in Gilt Silver Case signed ‘VULLIAMY’, 1823. Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy had three children, but none wanted to continue the family business. Although he became pessimistic about the future of British clockmaking in the face of growing international competition, he worked to protect the future of British Craftsmanship and industry. His support of the Company’s fledgling museum collection helped preserve the history of the trade, to which his own family had contributed significantly for so many years.

Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy: A Champion of British Craftsmanship is on display in the Clockmakers’ Museum at the Science Museum, Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London, SW7 2DD until the 2nd November 2025.

The post The Greatest Horologists You’ve Never Heard Of: Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy (1780-1854) – A Champion of British Craftsmanship appeared first on Worn & Wound.