Once again, Leap Day is upon us. This is an important day for watch lovers, particularly those of us who admire complicated watches, as it gives those lucky enough to own a perpetual calendar an opportunity to observe them doing the thing they’re meant to do. Unlike the vast majority of watches with any kind of calendar complication, a perpetual calendar has already identified 2024 as a leap year, and will summarily display the first day of March without the need to advance the date. This, of course, is quite a mechanical feat, and one that only comes every four years, so it’s absolutely worth celebrating an event that is as rare as the Summer Olympics, a United States presidential election, and a new Bad Boys movie, all of which, for better or worse, we’re getting this year.

This Leap Day, we celebrate the perpetual calendar by selecting a few of our absolute favorites. Our selections below represent many different approaches to the perpetual, from rigorously simple to intentionally complex, formal to sporty, and many places in between. The perpetual calendar might not be the most accessible of complications, but we can still appreciate them, particularly when they’re having their big, quadrennial moment.

Zach Weiss

I feel very strongly about perpetual calendars. I fawn over them. I look them up late at night when I can’t sleep and drool about the possibilities of knowing not just the day, or the date, or the month, or the phase of the moon, but knowing all of them and what year in the leap cycle we are in, not to mention the time, all at once—a glory I’ve yet to realize. I think, teary-eyed, about that moment, 11:59pm February 28th, on a leap year when – click – that magic extra day appears, an alignment only seen once every four years. The majesty of it all.

And then I think: I change my watch too often to keep a perpetual calendar running. They are notoriously fickle, especially during setting, and easy to break, and they tend to be anywhere from achingly to mind-bendingly expensive. I can settle for an annual calendar. Right? I should stick to the old triple. A day-date? Perhaps just a moon phase and a pointer…anyway. What truly draws me to the perpetual is not what they do, though that does intrigue, nor the mechanical solutions they employ, which does fascinate, but rather how they arrange all that information. The elegant or, at times, inelegant layering of hands, windows, indexes, discs, etc.

Needless to say, I don’t have a favorite perpetual calendar; rather, many I appreciate for specific reasons. A window here, a hand there. For example, the A. Lange & Sohne Lange 1 Perpetual Calendar places the month on a rotating ring, read at six, just beneath a tiny window with the leap cycle, and the day is via a retrograde pointer hand. So clever. Or the Patek Phillipe In-Line Perpetual Calendar that puts the day, date, and month into a single window. So clean. Or the Ochs Und Junior Perpetual Calendar that, to the uninitiated, perhaps looks more like a watch made by someone playing with their new drill press than an advanced calendar. I could go on.

But my task is to choose but one. ONE! Cruel. As such, I have to settle on the Breguet 3310. A maximalist approach to the perpetual, the 3310 places each element of the perpetual calendar on to its own sub-dial. Date at six, day at four, month at the center (weird, right?) under the hour and minutes, the leap year at eight, and the moon phase, inverted and set at an angle, up between one and two. But wait, there’s more, at half-past 10 is a power reserve indicator with a needle hand so long as to be nothing short of decadent. Oh, and there’s no running seconds because perpetual calendars are for those who think in years! In epochs!

Of course, this sumptuous display of calendrical madness is executed in a symphony of rose engine turned guilloché with various patterns interplaying within silvered brushed surfaces, beautiful typography, and shimmering heat-blued hands for a horological feast for the eyes. Yes, that’s one of the most ridiculous sentences I’ve ever written, but is it wrong? No.

But wait, it still gets just a little bit better. This remarkable and complex display of horology is 36mm in diameter, 8mm thick, and, yeah, it’s automatic.

Runner-up the Patek 3940 in white gold because it’s just the classiest damn watch ever to exist.

Zach Kazan

I have to admit something, and maybe it’s too transgressive for Leap Day, of all days, but I’m just going to do it: perpetual calendars don’t really do much for me. When I see a perpetual calendar, I see a bunch of things that I find unappealing on a whole variety of levels. I see an expensive object that’s prone to breaking. I see a toy for rich people, meant not so much to display the correct date and month, even on that very special day when the calendar does its thing, but to remind the world that they are, in fact, quite rich indeed. And I see a dial that is usually just too cluttered with small text that I can barely read for my own personal taste.

And yes, sometimes I see a beautiful object, a tasteful design, and a genuine mechanical marvel. And occasionally I see something that is actually kind of accessible in terms of ownership by a regular person. Do a deep dive on IWC perpetual calendars from the late 90s and early 2000s and you’ll see what I mean. Mostly, though, I don’t spend a whole lot of time thinking about perpetual calendars.

That said, when it comes to favorites there are two that come to mind. Yes, I’m cheating a bit here. But it’s Leap Day, which is a cheat of the calendar itself if you really think about it, so I hope you’ll forgive me. First, the MB&F Legacy Machine Perpetual EVO. Yes, I know I just said I don’t like a busy dial, so it’s a little strange that I’m picking what might read as the most chaotic watch ever made, but hear me out. Stephen McDonnell’s movement design is not just fully integrated (a rarity with calendar complications) but he went to great lengths to build in safety features that make it nearly impossible to break. That, to me, is truly impressive. And if you factor in typical service costs for perpetual calendars owned by morons like me who are likely to break them accidentally, it’s possible the EVO might even represent a good value with that six figure price tag (OK, maybe not). I also like that for a watch that is so complex in all the obvious and less–than-obvious ways, it’s still truly conceived as a piece you can wear everyday, with plenty of water resistance, a rubber strap, and a movement designed from the ground up with robustness in mind.

The other perpetual I’d like to highlight is on the opposite end of the spectrum of the MB&F, but one that I appreciate for similar reasons. The ochs und junior perpetual calendar is relentlessly simple, both in its unique display consisting of apertures filled by roving dots, and in its mechanics. Watchmaker Ludwig Oechslin’s perpetual calendar movement features just 9 additional parts over the base movement, with 3 modified parts, and approaches the perpetual calendar problem as one of gearing. Each part pulls double (or triple) duty, helping to solve multiple problems simultaneously. The economy with which ochs und junior approach their watches is a truly beautiful thing, particularly at a time when brands use the total number of components in a movement as a selling point. This watch is proof that there’s another, sometimes more elegant, way to do things.

Griffin Bartsch

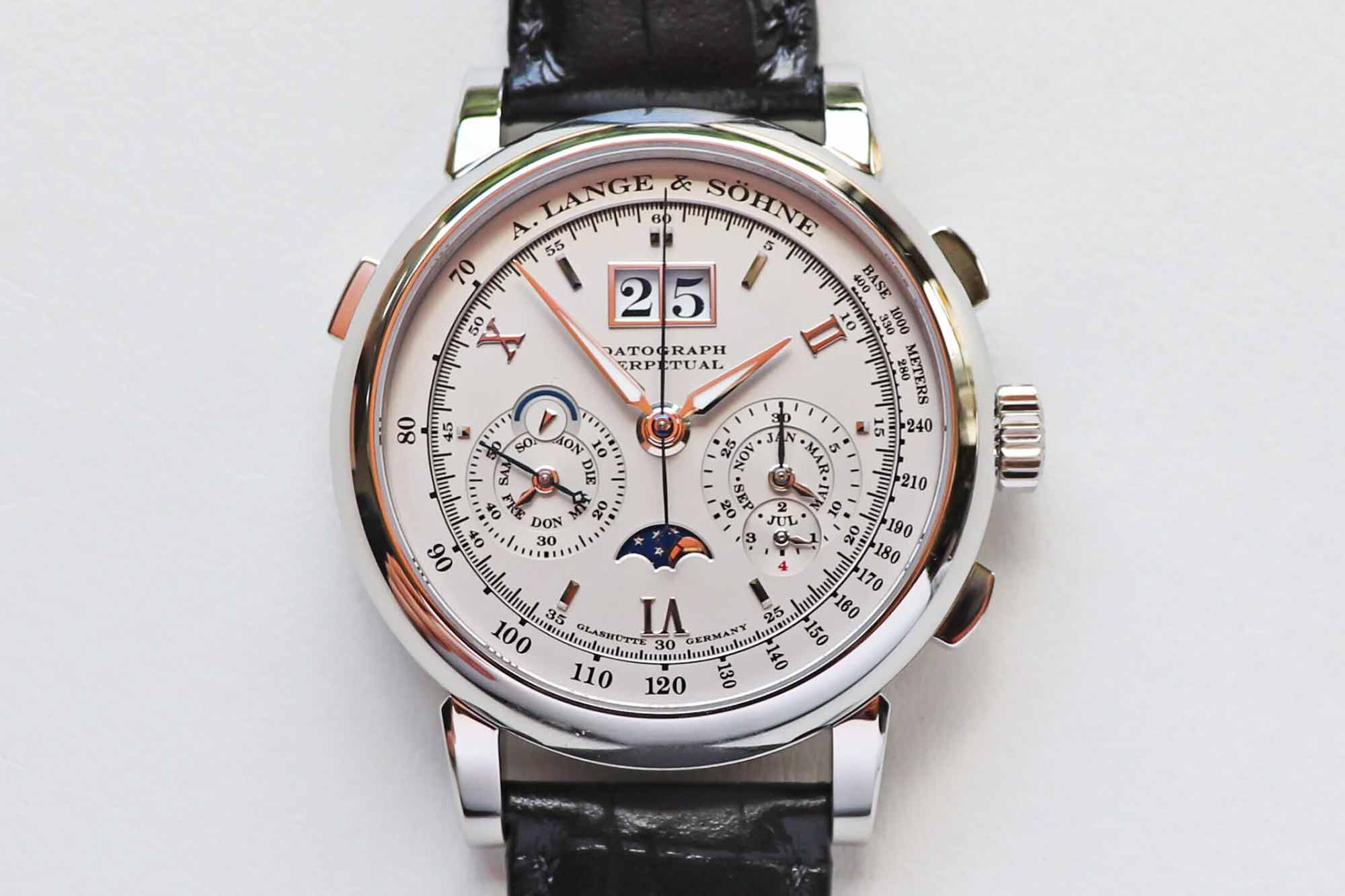

It’s hard to pick favorites. Ask me for my favorite book or movie, and you’re likely to get a different answer depending on the day, or even the hour. Ask after my favorite song and I could probably offer you a few options but would be hard-pressed to come up with any sort of answer. Ask who my favorite sibling is… okay, I only have one brother, so that one doesn’t really work. But ask me to pick my favorite perpetual calendar and you’ll have my answer before finishing the question. It’s the Lange Datograph Perpetual, all day, every day.

To be slightly more specific (because what is enthusiasm without unnecessary specificity), my favorite perpetual calendar is the first generation A. Lange & Söhne Datograph Perpetual 410.025 in platinum with silver dial. I don’t know that there is any watch I would consider to be perfect on all fronts — if there were, I’m not sure why anyone would wear anything else — but the Datograph Perpetual seems to me to be about as perfect a watch as any I’ve yet come across.

I’m not alone in my admiration for Lange’s chronograph series either; Philippe Dufour has called the Datograph (without the perpetual calendar) the finest serially-produced watch available and owns a ref. 403.031 in rose gold. The Datograph Perpetual takes everything that is great about that watch and turns it up to eleven. It’s beautiful, exquisitely finished, surprisingly wearable, and… undeniably very expensive. But you can have it for about a third the price of the newer Datograph Perpetual Tourbillon, and even isolated of price I prefer the earlier version — with its Roman numerals and more asymmetrical dial layout.

The whole concept of the perpetual calendar chronograph is, justifiably, tied to Patek Philippe. The 1518 was the first serially produced wristwatch to combine a chronograph with a perpetual calendar and that auction darling has set the template for most every QP chrono for the last half century. But for as good as so many other options are (I certainly wouldn’t say no to a Breguet 5617 in yellow gold) many feel a little generic. The Lange Datograph Perpetual stands out from the crowd as a watch that could only have come from Lange. And all else aside, I know I’d enjoy the inevitable reactions to my putting a $100,000 watch on a NATO.

Chris Antzoulis

Happy Leap Year! And Happy Birthday to those who only get to celebrate once every four years. Technically I have a watch case full of perpetual calendars, branded Casio, that I could offer up, but I thought I’d talk about something with a bit more oomph. Y’all can always count on me to go fun and colorful, so my favorite perpetual calendar to be tossed into the mix is the Moser Streamliner 6812-1201. If watch companies were high school archetypes, Moser would be the class clown slinging inappropriate comments and giggling when their life science teacher says “Uranus,” but is low key getting straight A’s the whole time.

This perpetual calendar is at once modern, minimalist, extravagant, technical, but in a uniquely Moser way. In fact, when glancing at this watch you would hardly assume it’s a perpetual calendar at all. Only upon closer inspection you begin to realize this dial has more to it than meets the eye. The smallest hand at the center pinion, that’s barely noticeable, is pointing at the month — with twelve o’clock representing January, one o’clock February, and so on. At four o’clock you’ll find the true jumping date indicator, which can be set forward and backward at any time, with no risk to the movement. On the left side of the dial is the power reserve indicator letting you know how much longer you have before your seven days is up, and you have to wind the manual movement. All this set on a beautiful smoked salmon dial, which I can tell you just shimmers in person. And yet, the true showstopper is on the back of the watch. Through the exhibition caseback you’ll see the stunning HMC 812 calibre, before your eyes move to the discretely hidden leap year indicator — a design solution that helps allow the minimalist layout seen on the front.

The Moser Streamliner has quickly become a modern icon for its retro-futurist design sensibility. Its unique case and bracelet shape are known to any watch enthusiast worth their salt, and now, Moser continues using the model as the basis for the brand’s evolution. If you’re looking to celebrate the leap year, you’re doing it with as much style and flair as anyone could possibly adorn if you’re fortunate enough to have one of these on your wrist.

Alec Dent

Any discussion of perpetual calendar wristwatches has to include the first to do it: Patek Philippe. My favorite, out of Patek’s very long history, is the reference 2499, a perpetual calendar chronograph with a moonphase.

It’s a watch with a storied history, thanks in large part to legendary musician Eric Clapton owning a platinum 2499 that has fetched multiple millions at auction. Other models in other metals and with less famous owners go for much less, but the Patek Philippe brand and the scarcity of the 2499–there were only 349 made during its 35 year run–mean that “much less” is still a lot of money.

The dial is a brilliant example of symmetry in design–two chronograph subdials at the 3 and 9 o’clock, a moonphase and date subdial at the 6 o’clock, and day and month windows at the 12 o’clock. Patek stuff a lot on the dial, but executed it in such a way that the dial doesn’t feel busy or overcrowded. The use of color on the watch is similarly inspired. The gold of the case, indices, and hands oozes luxury, and the blue of the moonphase subdial pops against the dial.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the watch is its size. Though the 2499 was first produced in 1951, Patek Philippe managed to stuff all of those complications into a watch only 37mm in diameter. But hey, that’s why Patek is one of the most revered watchmakers in the business.

Header image via Hairspring

The post Perpetually Yours: A Leap Day Guide to our Favorite QPs appeared first on Worn & Wound.