The Grand Seiko Media Experience is a whirlwind tour of several Grand Seiko/Seiko facilities across Japan. It’s designed to immerse journalists with a precursory knowledge of the brand in its culture, capabilities, processes, and goods while also giving a flavor of Japan itself. As one of four media invited to go last fall from the US and UK, I was delighted by the opportunity, but my goals were different, I believe, than those of my fellow attendees. You see, I am what you might call a Grand Seiko nerd.

I have reviewed several of their watches (such as the Snowflake and White Birch), served on a panel of their GS9 event, espoused my affection for the brand in a video with fellow Worn & Wound colleagues, and, perhaps most importantly, owned several of their timepieces (and still do). My goal during this trip was less to learn about the brand, though any information I could gleam would be valued, rather to further my appreciation for their craft and better understand the people who put my (and your) watches together.

Now, I could take you through each stop we made, every meeting we had, and each lecture or interview from an esteemed member of the Grand Seiko and Seiko ranks (including Mr. Hattori) we took, but I feel that article has been written. Instead, I want to tell you about how it affected me from the perspective of the Grand Seiko enthusiast I claim to be. And there will be lots of photos to show the rest.

The journey started and ended in Tokyo, a suitable place both for a trip to Japan (of which this was my first) and for one revolving around Grand Seiko and Seiko. The Seiko House Ginza, formerly Wako building, stands at an intersection of the heart of the neighborhood to which it shares its name. An old building that has been rebuilt and modernized a few times over the last century and more, it is a landmark of the area with its iconic clocktower and a fitting heart for the company (it was also under construction at the time, hence the lack of an establishing photo).

This was the first thing I learned: Seiko is still very much a brand with heart, literally and figuratively. It struck me the first day upon meeting with the team that was giving us the tour, as well as various executives, including Mr. Naito, the president of Seiko, and Mr. Hattori, the Chairman, Group CEO, and Group CCO of Seiko Group Corporation, and direct descendant of company founder Kintaro Hattori. It was palpable in the Seiko Museum Ginza and continued as a thread through the trip to the Shinshu and Shizukuishi manufacturing and assembling facilities.

During our stay in Tokyo, we visited the new Atelier Ginza, located within the Seiko House Ginza and where the Grand Seiko Kodo Constant Force Tourbillon is assembled. A prize of the brand, the movement’s designer helms the new studio, Mr. Takuma Kawauchiya, who gave us a walk-through of the watch and movement, something I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing more than once. In terms of the experience overall, it was a curious place to begin.

The Kodo is far beyond Grand Seiko’s fundamentals in concept and price. A proof-of-concept in practice, it shows the company’s capabilities while also making a statement about its willingness to pursue innovation in terms of engineering and aesthetics. That a relatively young watchmaker helms it makes a statement as well. Though a logical place to begin given its location, showing us the Kodo and the company’s newest studio first, it planted into our minds that Grand Seiko, despite its at-times-traditional trappings, is a brand with its eyes on the future.

“Always one step ahead of the rest” is Seiko’s slogan. It’s a saying that I heard repeated many times throughout the trip and one I’ve been thinking about since. There are ways, such as with the Kodo, Spring Drive, and the 9SA5, that Grand Seiko feels several steps ahead, yet they see themselves as just one. Perhaps that is a form of modesty or a way to keep the brand grounded. Admittedly, there are times when they seem the opposite too.

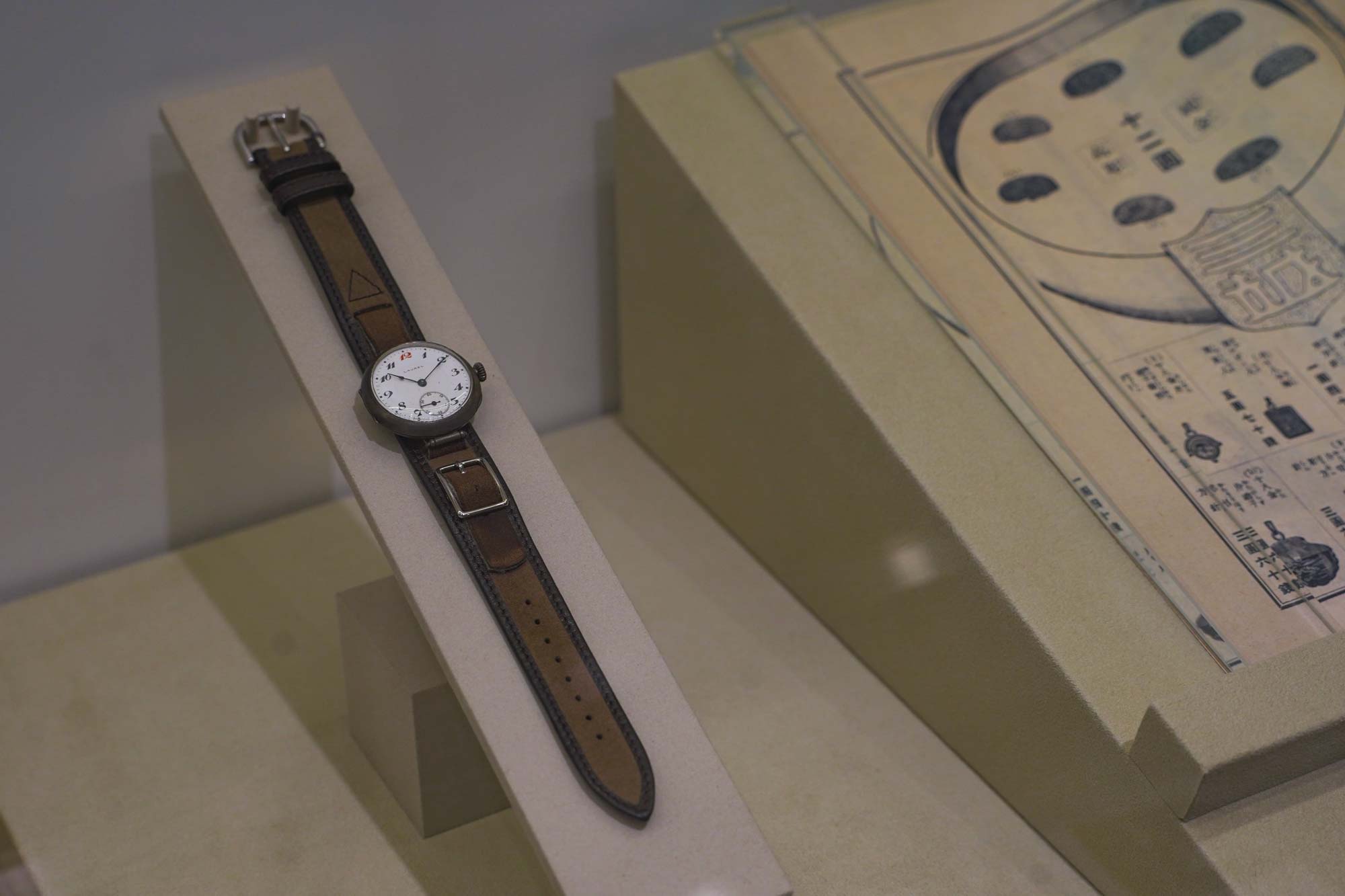

In contrast to the Atelier Ginza, we visited the Seiko Museum Ginza, which gets to the company’s roots and timekeeping. An unexpected highlight of the trip, the museum contained examples of Seiko watches and clocks ranging from the company’s beginning to modern times. But two things stood out to me there. The first was a lump of melted pocket watches.

On September 1st, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck Japan. It was a devastating natural disaster that resulted in over a hundred thousand deaths and fires that leveled Tokyo. Kintaro Hattori’s emerging business was also heavily impacted, but the company persisted, developing the first “Seiko” watch just a year later. As part of Mr. Hattori’s efforts to renew the company and give back to the ailing community, he released an ad to fix or replace pocket watches damaged or destroyed by the earthquake for free.

A move that seems mythical in terms of companies, the act of goodwill speaks to a brand that was greater than just selling goods. Pocket watches held more functional significance then than now for obvious technological reasons. Replacing them was truly a way to give back. That lump of pocketwatches is a tragic but potent symbol of this turning point for Seiko.

Part of what struck me, however, as a fan of the company, was that I didn’t know about this already. Though it likely has more local meaning, given the events that occurred, stories like this are the legends that build brands. Other companies in the world, say those who have some involvement in space flight, never miss the chance to remind you of it. I find it oddly charming that I had to go to a museum in Tokyo to learn this firsthand.

The other thing that stood out was not directly related to Seiko, but rather the history of telling time. Wadokei is a type of clock from the Edo period of Japan that is based on the seasons and the length of day. The clock features 12-hour units, six during the day and six at night. As the length of the day and night change, those units expand and contract. Functionally, this is executed by “regulating” the clock at sunrise and sunset. While difficult to synchronize, the poetic relationship between daylight, time, and the rhythms of how we live and work is profound, speaking to a more natural way of life.

Though the outcome is different, the heavy influence of nature and Japan’s micro-season structure are clear in Grand Seiko’s watches. While this was a cultural tie-in, nature is hardly Japan’s alone. But that a line can be drawn from a watch inspired by changing seasons to a method of living from centuries ago adds to the depth of meaning.

The Seiko Museum Ginza had floors of treasures to explore, which would take far too long to describe. It’s free and open to the public, so if you are a fan of Seiko and Grand Seiko and are in Tokyo, it’s a wonderful place to visit.

From Tokyo, we went to the factories where the watches were largely made and assembled. First was the Seiko Epson Shiojiri factory located in the Nagano prefecture, which houses the Shinshu studio. A place deep with Seiko lore, it began as Suwa Seikosha and is where the first Grand Seiko was created, Astron was born, Spring Drive was developed, and even Epson printers were created. Now, it is where all Grand Seiko quartz and Spring Drive watches are made, as well as Credor within the Micro Artist Studio.

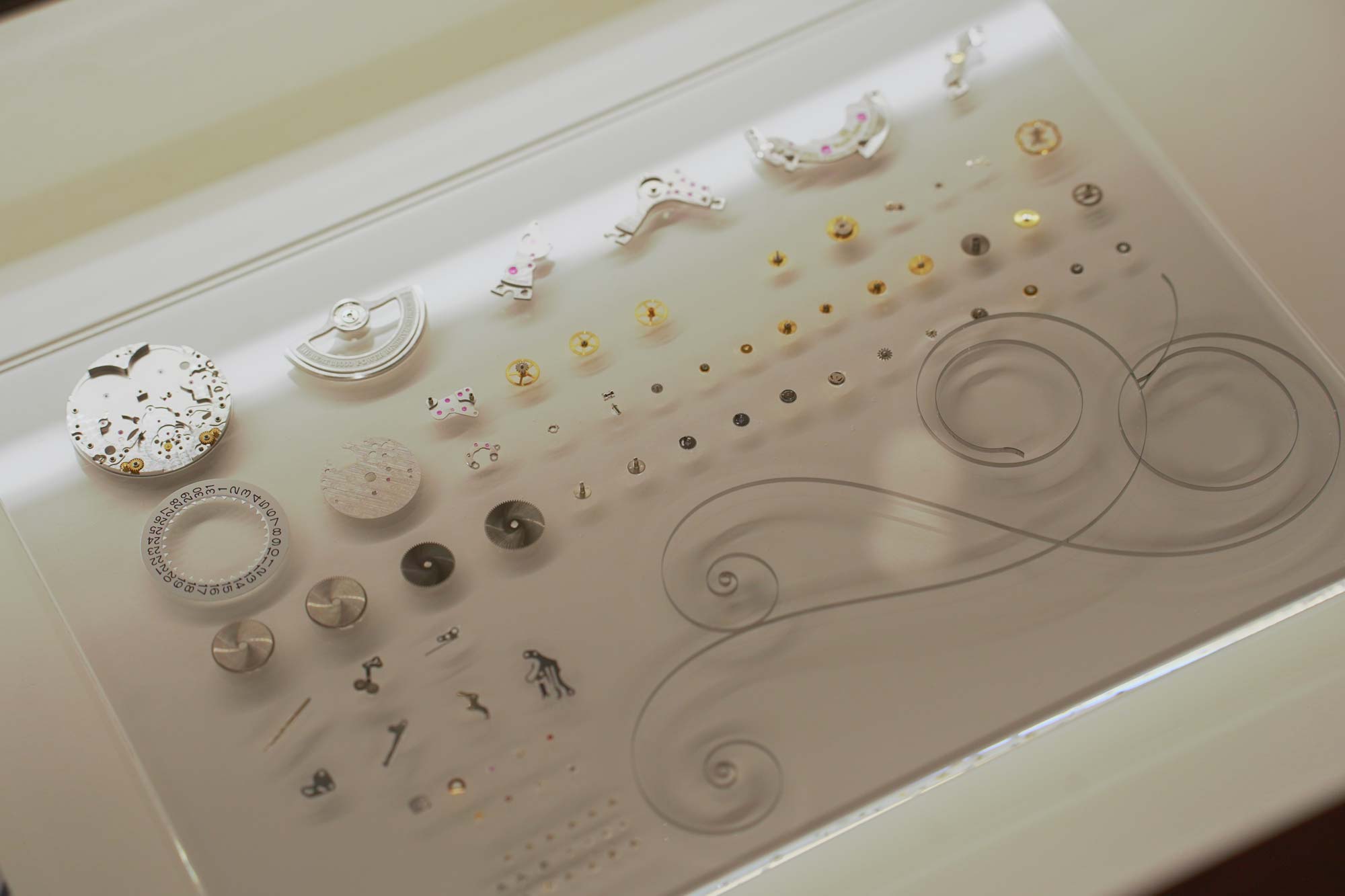

When one thinks about a “watch factory,” this is what they imagine. Room after room, floor after floor of production ranging from dial printing to marker polishing to case finishing to movement assembly to diamond setting. If you want to see how Grand Seikos are made, though the mechanical watches are made elsewhere, Shinshu shows you how.

As someone who got into Grand Seiko via a Spring Drive watch, my beloved SBGA375, this was a particularly meaningful portion of the experience. This isn’t the place, I think, to wax poetic about Spring Drive, but I do think it’s truly profound watchmaking, especially as it’s combined with rigorous, handmade details. The term “Zaratsu” polishing is often thrown around in reference to Grand Seiko. It’s a method of mirror polishing using a specific type of machine. I chose the 375 as my first Grand Seiko because it features the 44GS case with large swathes of Zaratsu polishing. But seeing it in action made it all the more remarkable.

As luck would have it, they were polishing 44GS cases (perhaps this was careful planning and not luck, but either way, I was very excited about it). Finishing is a fairly brutal process. The machines are loud and smell of oils. They can rip things apart. Zaratsu polishing requires skill, as a wrong move can instantly ruin a case. The balance between elegance and destruction, which is navigated by skilled hands, is why these things matter. Seeing how the artisan moves with speed, efficiency, and grace, polishing each facet of each case, and then checking them for imperfections was awe-inspiring. The lore is actual, I got to see it in action. The scratches in my 375 looked a little deeper that day.

Certainly, one of the points of the Grand Seiko Media Experience is to prove that what is said is real to those on the tour so we can then spread the gospel. As consumers of watches and other luxury goods, we are told what goes into making a product and what makes it of value. There’s a lot of “trust us” sentiment in that, as we don’t get to see behind the curtains. Part of that story for Grand Seiko is the level of craft that goes into each watch, which exceeds what one would expect at their price point. That’s all well and good on paper, but unlike most brands, Grand Seiko does let us in.

The rest of the factory tour continued this level of transparency. We stood what felt like right behind (though we were on the other side of glass) as dials were pad printed and movements were assembled. We entered the room as Credor Eichi II dials were being polished and hand-painted with the utmost care. I was shocked by the fact that we could go into the stonesetting area at all (which I expressed to our guides and was met with amusement and some confusion). We watched as hands were heat-blued with perfect timing (one instant either way would affect the color).

The Seiko Epson factory isn’t new; it has a lived-in feel. It’s not “luxurious” like the product they make (or their sibling site at Shizukuishi, but I’ll get to that later), but it has a warmth to it I wouldn’t expect in a factory. Each area felt like a neighborhood unto itself. Most of the people who worked there have long careers within the company or are on their way there. They felt like part of the building. A patina of a different kind. This goes back to that sense of “heart” I spoke of before. Factories can be cold and soulless, but this wasn’t at all. I don’t know if that makes for a better product, but I’d like to think it does.

Several hours on a bullet train a day later made me feel ashamed of America’s rail system, but thankfully, we arrived at our destination, and watches re-filled my thoughts. We’d made our way up north to Morioka to visit Shizukuishi. Dedicated to their mechanical watches, Shizukuish is Grand Seiko’s newest facility.

Designed by famed Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, Shizukuishi expresses a different side of Grand Seiko. Mr. Kuma’s work is known for using light and natural materials to create buildings that are at once modern and elegant, combining organic and synthetic forms. The visual comparison to Grand Seiko, if not literal, is easy to conceive, such as on the SBGA413 “Shunbun.” However, it’s the conceptual relationship I find more interesting.

I’m a firm believer in aesthetic taste. Though a term that is hard to fully define and full of subjectivity, it can mean an individual’s preferences towards particular sensory input and a judgment thereof. Hence “good” taste versus “bad.” While luxury goods are often grouped as objects of good taste, many don’t, or shouldn’t, fit the bill. They can be garish, tacky, or purely successful due to an illusion created by strong branding and celebrity endorsement. While I acknowledge how subjective this is, I believe a large portion of the appeal of Grand Seiko is rooted in an undeniable sense of good taste.

They mix modesty with craftsmanship, high-spec movements with playful textures, and, most importantly, have a vocabulary of design (literally) that sets them outside of other watchmaking traditions. Grand Seikos, from an “entry” 9F quartz to a 9SA5 powered White Birch (or, frankly, the Kodo), have these features. They have a quiet confidence and refinement that, as an owner, you wish to echo. This is at the root of my appreciation for the brand.

The relevance here is that the architecture of the Shizukuishi studio demonstrates these qualities in a subtle and effective manner. Shinshu shows you how Grand Seiko was made and where it came from. It’s an indelible and relatable part of their journey. Shizukuishi is where Grand Seiko is headed. It’s ascended and ethereal, a building that perfectly reflects the brand’s values.

There was heavy rain on the day we visited Shizukuishi. Perhaps not the ideal weather they had hoped for, as the view of Mt. Iwate that has inspired so many dials was obscured behind fog and clouds, but I was into it. There was a serenity to the structure that was emphasized by the sound of rain hitting the roof and dripping off beams in small waterfalls. The lush green surroundings, which were enjoyable through the full glass exterior, are a point of pride for the brand and had a deeper tone of green because of the moisture, adding to their luster.

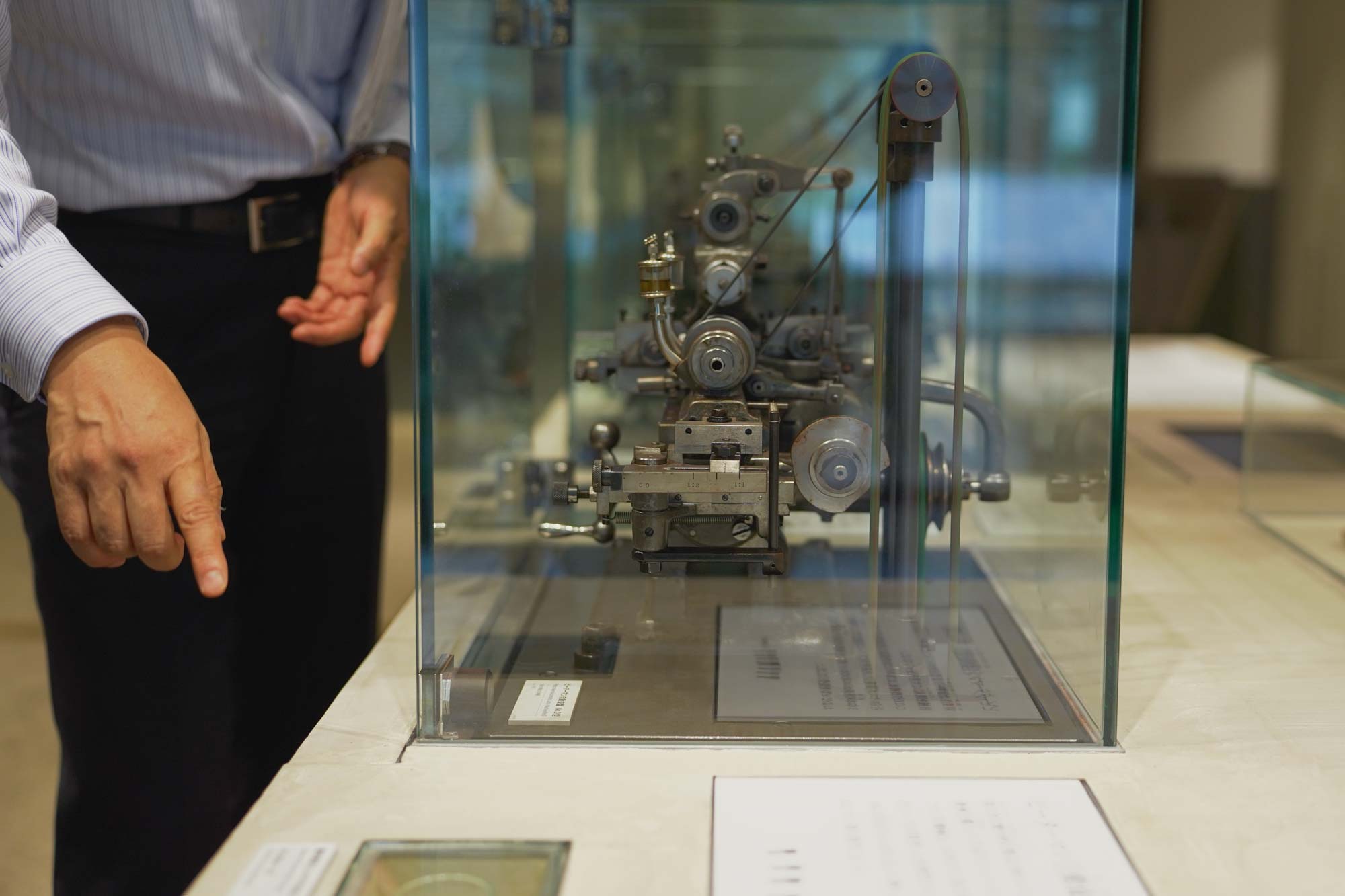

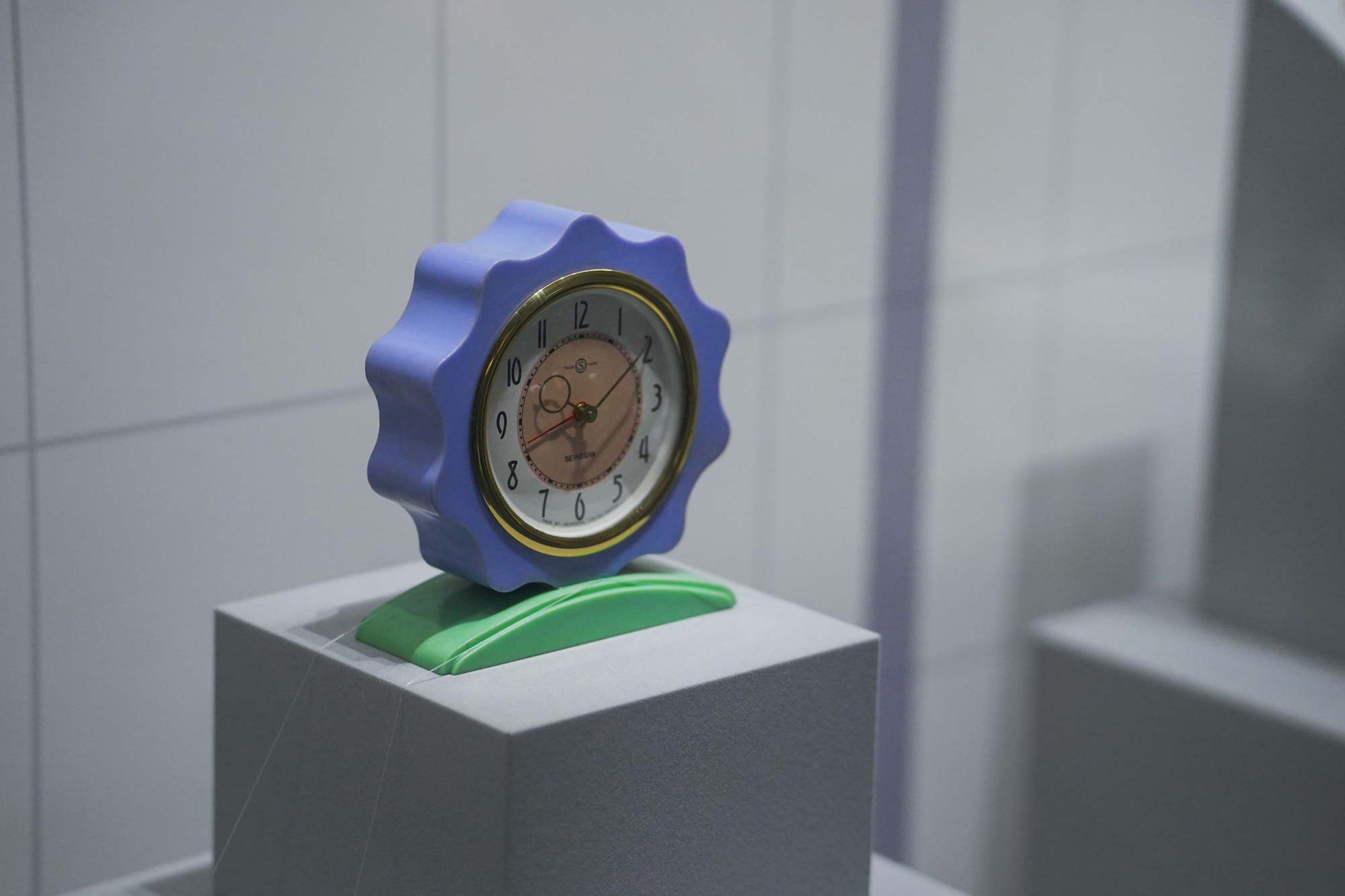

The entry room of the building contains an exhibit dedicated to the past and present of Seiko and Grand Seiko, complete with a Laurel from 1913. The vitrines continue to the mechanical movements of Grand Seiko, with all current calibers on display, from the manual wound 9S63 and 64 to the newest dual-impulse models, the 9SA5 and C5.

Unlike Shinshu, Shizukuishi’s working area occupies a single floor with one large room full of watchmakers. Here, they assemble movements and watches but do not do any of the manufacturing. We viewed this room from a hallway on the other side of glass to maintain the cleanliness inside. Though less tactile and immersive than the tour of Shinshu, witnessing the assembly was still enjoyable. This was largely because of the watchmakers and the guides themselves.

My biggest takeaway, particularly as a fan of the brand, was that “heart” again. The facility had a genuine feeling of enthusiasm despite being newer than Shinshu. It was full of watchmakers working together, quite enjoying what they do. They even have a mentorship program that facilitates the transfer of knowledge and skills from one generation to the next, which likely builds a tighter community as well. The people we met were quick to laugh, open to our presence, and generous with information.

In contrast, I’ve been to European facilities where, despite being a guest, I felt like an intruder and an interruption. Liking the people at a brand isn’t necessary for a watch collector. Most of the time, our familiarity with the people doesn’t go beyond retail representatives. Meeting the people behind the brand opens it up further, for better or worse. In the case of Grand Seiko, it was genuinely for the better. The people who likely made the very watches I own are happy and nice. I can’t help but like the watches more for it.

The tour ended with a lecture on their movements, particularly the 9SC5 and Tentagraph watch, and a brief Q&A with 9SA5 designer Mr. Hisashi Fujieda. It’s been almost four years since the 9SA5 was launched, and it was great to be reminded of just how special of a movement it is. I’d go so far as to say that Grand Seiko could remind us of that more regularly. It’s a 36,000 bph hi-beat movement with an 80-hour power reserve, a proprietary escapement, an overcoil with a proprietary adjustment system, a unique winding system (the off-set magic lever), a pleasing design, and nice finishing. If they were Swiss, they would charge far more for it. But I digress.

Brand’s on the scale of Seiko can feel impersonal. That’s not an intentional thing; it’s the side effect of being a large and relatively old corporation. In my experience, when visiting larger watch companies on their home turf, though they might have a core team that brings some warmth, the companies still feel like machines. That family feeling is gone.

While internationally, it might not be as clear, Grand Seiko and Seiko feel like a surprisingly tight-knit company once in Japan. The people are friendly and approachable, from the craftspeople and watchmakers in the factories to the C-level executives. It’s a large company that manages to feel small in the right ways. It’s personable. The fact that a descendant of the founder still walks the halls probably helps with this.

Snobbery often follows from luxury, so much so that the words can sometimes be synonymous. I didn’t feel an ounce of snobbery on this trip. That might not be the point of the experience at large, but it’s important to me as a brand collector. Sure, the watches are beautifully made, each touched by talented hands, but they don’t act above anyone else for it. As such, those who collect them shouldn’t either. A watch should reflect its owner and their tastes, and if humility is an attribute of the brand and its watches, then they are worth collecting.

I’ve left out all of the fun stops in between as I intend to save them for another post, but needless to say, there were more than watches on this trip. As the name suggests, it was an “experience.” We returned to Tokyo for one last evening, including a few hours of alone time in the city. The rain was heavy, so I stayed in Ginza, but I did end up with a few souvenirs, one of which adorned my wrist on the way home, but once again, more on that to come. Grand Seiko

The post The Grand Seiko Media Experience: An Enthusiast’s Observations (with Photos!) appeared first on Worn & Wound.